October is awesome. Savoring each beautiful day. Like a harvest basket, today I’m sharing a mix of topics gathered over the past month or so. May they nourish.

As always, thanks for reading and being a loving presence in this world.

“TOURISM ATE THE BLOCK”

My recent piece, “Tend-er tourism in a time of terror,” which focused on destination stewardship, included the important admonition that “tend-er tourism centers truth, reconciliation, and reparations.” In their October 10, 2025 e-newsletter, the Reparations Stakeholder Authority of Asheville (RSAA) shared a Black perspective on the topic of tourism (using the title above), which I’m quoting in full, with permission:

“Asheville sells itself as soulful, but behind the murals and craft beer sits a truth this city refuses to name. The economy feeds on Black culture while erasing Black people. Downtown murals become postcards for visitors while the descendants of the people painted are pushed out of the frame. Pop up menus market our flavor while the restaurants that carried us for decades are priced into extinction. Breweries land on gentrified blocks and pour profit into white hands while siphoning life from the neighborhoods that built the city’s rhythm.

Hotels rise where our homes stood. Short term rentals swallow blocks and strip housing while Black families fight eviction and pay rising rents on flat wages. Visitors come to experience Black Asheville, but the people who are Black Asheville are pushed to the margins and staged as props for someone else’s weekend. This is not revitalization. It is cannibalism dressed as commerce.

Southside, Burton Street, Valley Street, and East End carry the record in the ground. Redlined, renewed, then gentrified. Condos replace Black businesses. Families scatter. And still we resist. Community gardens feed where chains refuse to build. Black artists claim walls that outlast the paint. RSAA and partners hold space where joy is practice. At 690 Haywood a house for repair rises.

Repair here is measurable. Return land and stabilize rent. Unbundle city contracts so Black firms can lead and get paid on time. Dedicate a share of tourism taxes to Black housing, Black enterprise, and Black cultural stewardship under Black governance. Repair is not a festival or a mural. It is Black Asheville living here, owning here, profiting here. Until then, every poured pint is another receipt of what this city has taken. When repair is real, the receipts run the other way.” [end quote]

Cosign all the way.

Here’s a short video from the 2025 RSAA Sneaker Gala:

If you’re not on the RSAA e-newsletter list, you can sign up here (click “Learn More” at the bottom of the page. You can make a donation as well.

THE REMNANTS OF RACE RECORDS

A related topic is cultural reparations. In this case, musical. With an upcoming record release and weekend of events and celebrating the centennial of The Asheville Sessions, it seems timely for me to return to reflections about the history of Appalachian music.

A centennial event webpage says, “If the 1927 Bristol Sessions that came two years later are remembered as the ‘Big Bang of Country Music,’ the Asheville Sessions lit the fuse. They proved the mountains were full of music the world needed to hear, and they set the stage for the explosion of American roots music that followed.”

It certainly did set the stage for what followed. All of the musicians who were recorded were white and male*. Thus, despite their documented participation in the creation of this music, none of the artists recorded were Black. For context, in 1920, Asheville was 25% Black, which grew to 28% by 1930 (14,255 of 50,193 residents).

The Asheville Sessions were “Ralph Peer’s first field effort to document and market rural Southern music near its source” (centennial webpage).

As noted in Ballad of America’s The Making of Appalachian Music, around 1923, when Peer first “began to record rural White musicians, he declined to list their releases in Okeh’s general catalog, surmising that rural records would have only niche appeal. To accommodate performers like [Fiddlin’ John] Carson, therefore, the category of ‘hillbilly’ records was invented.”

While The Asheville Sessions encompassed a wide range of genres, with the rural framing and racial composition of the performers, I believe the recordings fell more in the ‘hillbilly’ category overall, as compared to Black or “race” records.

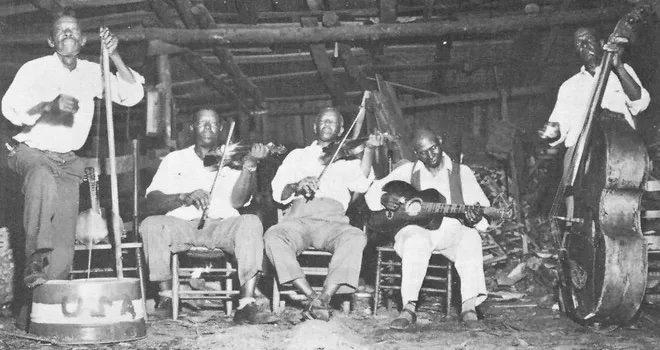

As Ballad of America explains, “The designations of ‘race’ [Black] and ‘hillbilly’ [Appalachian], like musical genres today, were marketing categories, designed to connect consumers with music that they could expect to enjoy. However, these categories did not reflect actual musical practice, which was not divided neatly across racial lines. Just as White musicians often sang the blues, Black performers played fiddle and banjo, formed string bands, and sang sentimental songs. Indeed, Black fiddlers were foundational in the development of Appalachian playing styles, and the banjo is an Afro-Caribbean instrument.”

“The segregation of rural musicians into ‘race’ and ‘hillbilly’ categories…meant that the music of Black Americans was excluded from the emerging Appalachian soundscape. By necessity, social constructions of music genres said that if music was ‘Black,’ it could not also be ‘Appalachian’” (Ballad of America).

The scope of that cultural loss overwhelms me.

It’s another moment of multiple truths, as we honor the fact that The Asheville Sessions were, “a pivotal moment as traditional Appalachian music was beginning to evolve into the emerging commercial genre that would become known as country music” while grieving the multitude of cultural losses. The keyword is “commercial.”

This grief is a topic I’ve addressed before, particularly in Repairing narratives: old-time and bluegrass music (2019), and in the “Affrilachian Music” section of Holding History (2017), and in Reckoning with cultural extraction (2019, available as a zine). I’m trying not to retrace my steps too much here. For those who want a deeper dive on this topic, in addition to the resources linked in those pieces, I’ve created an evolving Are.na page of articles, etc. about the Black Roots of Appalachian Music.

When I think of Asheville’s cultural identity, The Mountain Dance and Folk Festival, which was founded by Bascom Lamar Lunsford in 1930, has played a large role. Prior to that, he was one of the artists recorded during The Asheville Sessions. The festival has influenced what we consider to be roots music and dance (and thus musicians and dancers) from this area. At times the event was promoted as featuring, “Pure Anglo-Saxon Music,” which we know is false (Phil Jameson, et al).

We also know that, “although Lunsford collected music from Black informants and reportedly spoke well of them as individuals and performers, no Black musicians ever took the stage while he led the festival” (Ballad of America). I’m not sure how many have since, I suspect it’s a very small number. There are certainly positives that came and continue to come from the Mountain Dance Festival. Particularly how it encouraged heritage tourism as compared to what was an eventual shift to a focus on hospitality tourism (see Katherine Cutshall’s research). However, the racial exclusion was damaging.

Beyond that long-standing festival, I think about all the ways our cultural and musical story has been told over the years in tourism narratives and the like, almost all written by white people. Also framed with a commercial bent in mind.

This centennial could be a moment where institutions double down on an old, incomplete story. Or perhaps it can spark nuanced conversations that will lead towards actual action to repair the damage caused by this historical musical segregation and erasure.

At every juncture, we have the opportunity to make programmatic and storytelling choices that acknowledge harm done, provide reparative resources, and expand education and opportunities for current and future Black Appalachian musicians.

Rhiannon Giddens has done so much to amplify the Black history of roots music, including curating the Biscuits & Banjos Festival this spring, which was “dedicated to the reclamation and exploration of Black music, art, and culture in her home state of North Carolina.” I love “What Did the Blackbird Say to the Crow,” an new album of North Carolina fiddle and banjo music that she recorded with her former Carolina Chocolate Drops bandmate Justin Robinson. Sankofa for sure.

RIVER REVEALATIONS

In episode 5 of Temple of Seaweed’s Wailing Earth series, “The Swannanoa Speaks,” we experience a poetic journey of grief, beauty, and grappling with a river’s perspective. It’s yet another reflection in the kaleidoscope of artistic responses to Hurricane Helene.

It’s described as, “an immersive nature documentary about the 22-mile Swannanoa River Corridor, chronicling the river’s tenuous reality and the tender love of the people who call its banks home. In the aftermath of Hurricane Helene, the National Trust for Historic Preservation declared the Swannanoa River Corridor one of the most endangered. historic places in America. ‘The Swannanoa Speaks’ considers what the river longs to say to us.”

Watch:

Wonder. Water. Weaving.

HELP SHARE THESE WRITINGS

Hey sweet readers, I hear regularly how these writings are helpful. If that is true for you, please share my work with others who may benefit. I’ve turned off social media so this email list is my/only main outlet, along with the fact that these pieces live on the Writings page of my website. Any support with sharing these around Asheville and beyond would be a gift. Folks can subscribe at amiworthen.com, or send an email to me to add.

* I focused on race in this piece, though gender and the music business is another equally important story to explore, particularly with an intersectional lens.

Onward. More next month.

I love this. Thank you for sharing. A couple of weeks ago I had the pleasure of attending the Hook and Line Festival in Mebane and heard Rhiannon and Justin and others perform.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you, and I bet that was awesome!

LikeLike