June in WNC is, as always, magic. Verdant, warm, sweet. The bliss of sunny days by the river. Garden gifts. Evenings where the blinking lights of fireflies are nothing short of miraculous. This June people have been taking to the streets to protest the abuse of power. They also are lights, also miraculous.

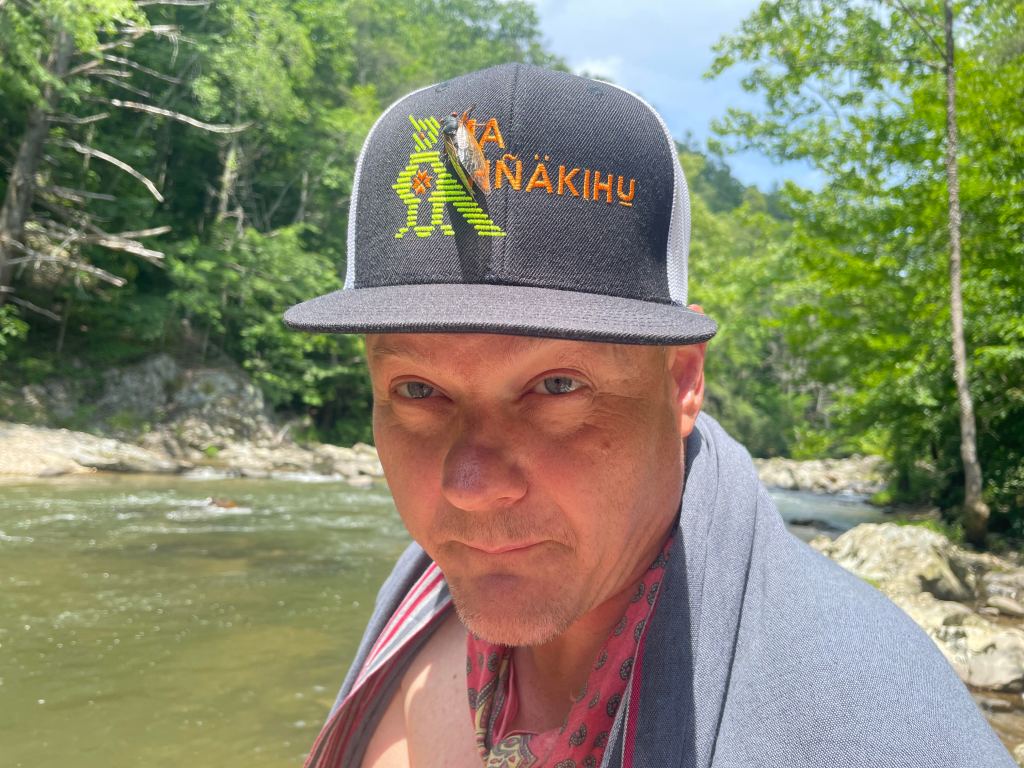

The 17-year cicadas continue to intrigue me. On a recent river day I was happy to have photographed a member of Brood XIV sitting on Jason’s Mä hñäkihu hat. I love how the cicada’s orange matches the orange of the logo of this Indigenous initiative.

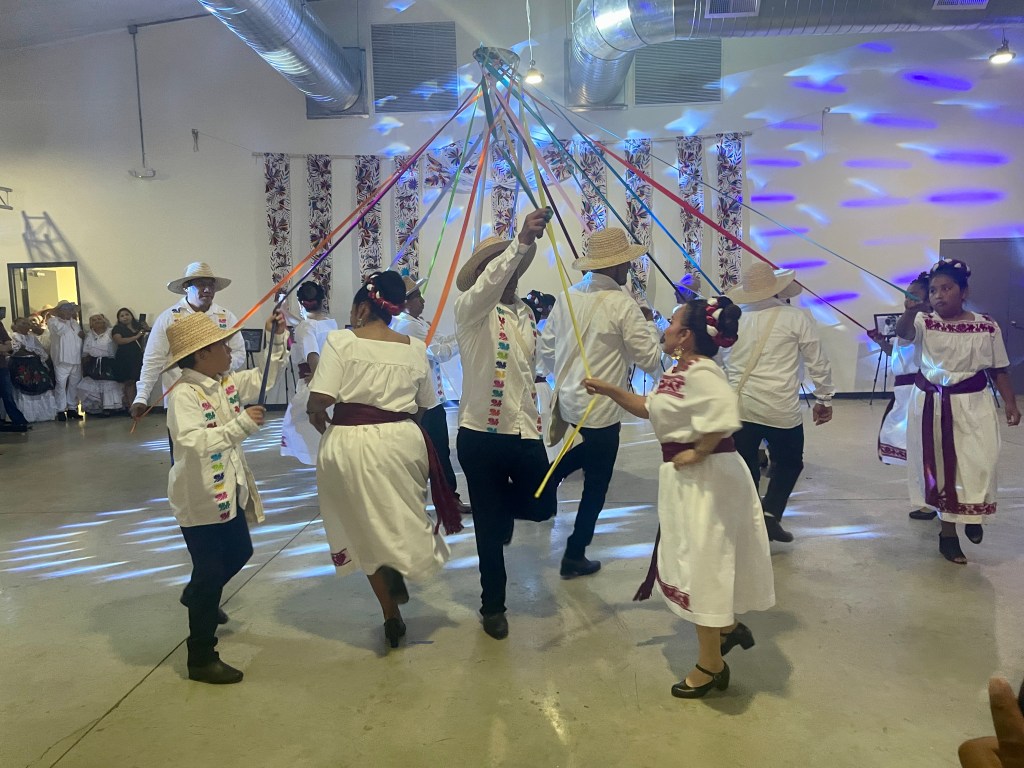

Mä hñäkihu is a Hñähñú language and culture preservation project based in Emma, Buncombe County, NC. They offer classes and events for the significant Hñähñú population in that community, whose roots are in the Mezquital Valley of Hidalgo, México. Mä hñäkihu also collaborates with other Indigenous people in the area, including the Cherokee, and with Hñähñú communities in Florida and México. In addition to in person offerings, they post teaching videos online (one of which went viral recently). Of note is the fact that Hñähñú people are sometimes called Otomí, which is the name given to them by the Aztecs, though their roots are even older.

Jason and I have had the honor of working with Mä hñäkihu, me in my behind the scenes way, and him helping with their musical activities. We’ve both learned so much from their orientation to time and culture.

Time is long. Culture is critical.

These concepts were reinforced by an interview I recently listened to with Chris La Tray, “How to be a Dissident: Learning from Indigenous Resistance and Resilience” on the new co-regulation podcast, hosted by Holly Whittaker (1). I’m going to excerpt here, but I definitely encourage you to listen to the whole episode.

La Tray is a descendant of the Pembina Band of the Mighty Red River of the North, a member of the Little Shell tribe, and the poet laureate of Montana. In the interview, he emphasizes the scope of his people’s history on this continent, which is over 15,000 thousand years, as compared to the settler colonist history of around 500 years. A tiny blip on the timeline.

One of the most moving parts of the conversation is when he describes a visit to the La Brea Tar Pits in L.A. at the time of an eclipse, and visiting the museum which has skeletons of “mastodons and North American camels and saber-tooth freaking tigers, and this whole wall of skills of actual dire wolves” (2).

“And they’re all extinct now,” he says. “That world is gone. And it was beautiful and spectacular and it’s gone. And now we have our world. It’s replaced that. And for all the shittiness and all the things that we can sit here and focus on how terrible it all is, this moment together is beautiful…”

“And, you know, now we are on a path where maybe we can destroy all that. And that sucks. But this experience there gave me some kind of peace about it, because even if we do that, if we just reduce the world to cinders, something else is going to come back.”

“But then, I started thinking about, well, who isn’t extinct? Who hunted those relatives with sharpened sticks? You know, we did.”

“We were there, and we’re still here. And in Anishinaabemowin, our language, there are word pieces that we know were spoken by those people, by people who lived and had good lives.”

“And it made me just feel like, you know, I want to be part of whatever it is that we need to do to ensure that whatever that next beautiful world is, because it’s coming, we’re not going to live like we are now. We need to be there on the other side.”

Yes! I found such solace in his words. When I am discouraged or overwhelmed, it always helps to stretch the temporal context of my work. I am a link in a long chain pulling us towards liberation. I am also the product of settler colonists who sought to destroy Indigenous life on Turtle Island. While my people did extreme damage, Indigenous people and wisdom survived, and now I have an opportunity to be part of the repair of that damage.

I love supporting Mä hñäkihu and their efforts to ensure the Hñähñú language does not go extinct, that their culture continues to be a living practice and not a skeleton in a museum display. There are many Indigenous-led groups doing vital work. Examples include the Center for Native Health in nearby Cherokee, and the Native Land Conservancy in my birthplace of Massachusetts.

Efforts to bridge the ancient and the still unknown.

In his book Love and Anger, Lama Rod Owens writes, “With all of this apocalypse talk, people think it’s about the end of the world. It’s not about the end of the world – it’s about the end of way of thinking, a way of believing, and that’s painful to let go of. That’s where the fire and brimstone and the end of the world metaphor comes in. It’s from the basic tension and fear of letting go of the ways that used to be, in order to make space for what’s happening next. What’s happening next is terrifying because we don’t know what it is, it’s a mystery.”

So we lean into the mystery, and the essential role of radical imagination in creating the next beautiful world.

Meanwhile, we can also change how we interact with this one.

Noting his certainty of a better future, Whittaker asks La Tray, “I know people are being moved, but I also don’t necessarily have the same optimism that you might have. Can you talk about like, what’s going to actually get that? Like, why are we not there? How do we get there?”

“I don’t know how to answer that. You’re exactly right. People don’t want to relinquish their privilege and their convenience. I mean, what if we all of a sudden just stopped doing all the things like going to Target? Or what if we all canceled our social media or our Netflix and all of these things?”

“You know, that little group of dudes who were sitting behind Tr*mp when he gets inaugurated, all those tech billionaires, what if we just stopped? And for three months, what if basically what happened to Tesla happened across the board to all of these places? That is a level of power that we have that is a very easy thing. Yet people are like, well, you know, I’m not going to cancel my Netflix, that’s my source of happiness.”

“It’s like, well, you got to relinquish some of that, at least for a period, you know? So simple choices like that, easy to make. We were having a discussion in my class last night and a number of students were dumbfounded about how Tr*mp people can still be supportive of him. Like, ‘don’t they know this? Don’t they know that?’ And I was like, ‘don’t you know your cell phone is upholding slave labor in other parts of the world?’ All of the things that we choose to participate in.”

“So how do we get people to relinquish those things? That’s hard. And I think we do it by doing it ourselves and not wagging fingers, but just saying look, if you want a solution, here is a solution. Here’s a very small, easy thing you can do. And who knows what the result will be.”

While it sounds simple, I understand the challenge of what he’s proposing, even as it is a clear way to exert our collective power. We do what we can. Creating what’s next takes a myriad of strategies and solutions. Some of us will be in the streets, others in the spreadsheets. Blinking our fleeting lights.

Dear readers, thank you for all you are doing and dreaming and being for now and the future. I’m grateful we are on this journey together.

1. A friend recommended Holly Whittaker’s book, Quit Like a Woman, to me because so far in 2025 I’ve avoided drinking alcohol. In it, she offers a feminist lens on sobriety. Because of my abstinence, I’ve been doing a lot of reading and thinking about the impact of drinking on our lives – such a big, interesting topic!

2. Somewhat related, I was super excited to learn about the Appalachiosaurus, a regional dinosaur for some reason I’d never heard about before. Wild to picture it running around.